You’ve probably seen animated characters that look stiff or lifeless. The missing ingredient? Most likely, the 12 Principles of Animation. Developed by Disney legends Ollie Johnston and Frank Thomas in the 1980s, these principles are the backbone of animation. Whether you’re animating in 2D, 3D, or stop motion, they give your work rhythm, clarity, and believability. Think of them not as rigid rules, but as trusted ingredients—like salt and pepper in cooking. You don’t need all of them in every dish, but knowing how to use them changes everything.

The 12 Principles

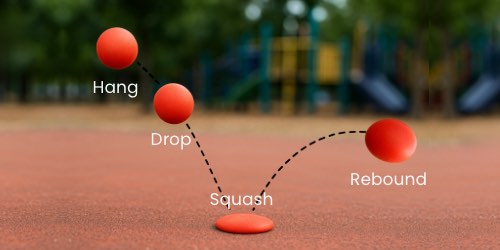

1. Squash and Stretch

This is the foundation of believable animation. A bouncing ball that flattens on impact and stretches as it rises instantly feels alive. It’s about preserving volume while showing flexibility. Picture a water balloon hitting the floor—it squashes wide but never loses its “fullness.” Animators use this principle to add both comedy and realism, from Pixar characters’ faces squishing mid-laugh to Spider-Man’s limbs stretching dynamically during a leap.

Getting this right teaches you weight and timing more than any other exercise. Practice with a bouncing ball, and you’ll see how even simple motion comes alive with squash and stretch.

2. Anticipation

Before every big move, there’s a smaller setup. A pitcher winds up before the throw, or a character crouches before a jump. Anticipation builds clarity and energy. It signals the viewer’s brain: something’s about to happen. Without it, actions feel sudden or awkward—like skipping the inhale before blowing out birthday candles. Think of Elsa in Frozen, sweeping her hands back before creating ice; that pause makes the action magical.

3. Staging

Staging is about directing the audience’s attention. It’s the same principle stage directors use—lighting the main actor while everything else fades. In animation, that means clear silhouettes, uncluttered backgrounds, and purposeful timing. A character delivering an emotional line should be framed and timed so the viewer can’t miss it. Think of Simba silhouetted against the sunset in The Lion King. The scene is simple, but the clarity makes it unforgettable.

4. Straight Ahead Action and Pose to Pose

These are two different workflows. Straight ahead means animating frame by frame in sequence—great for fluid, chaotic actions like fire or hair. Pose to pose means drawing key positions first and filling in the gaps—ideal for dialogue and story-driven acting. Animators often mix both, using strong poses for structure but adding fluidity with straight-ahead details. For instance, in Moana, Maui’s hair often flows “straight ahead” while his body animation is carefully posed.

5. Follow Through and Overlapping Action

When motion stops, parts of the body keep going. A runner’s arms and legs halt, but hair, clothing, or even a tail continue a beat longer. Overlap makes characters feel organic rather than robotic. Imagine Wile E. Coyote running off a cliff—his body halts mid-air, but dust, limbs, and ears trail behind before gravity takes over. The humor and realism both come from this delay.

By layering follow-throughs and overlaps, you give audiences a sense that your character has weight and elasticity, even in cartoony worlds.

6. Slow In and Slow Out

Objects don’t start or stop instantly; they ease in and out. More drawings near the beginning and end of an action create this natural acceleration and deceleration. Without it, motion feels mechanical—like an old flipbook toy. Think of Buzz Lightyear lifting off in Toy Story: the hover and slight delay before speeding up makes the flight feel powerful and believable.

7. Arcs

Most natural movements travel along arcs, not straight lines. Arms swing in curves, balls follow parabolas, and heads nod on gentle arcs. Straight paths look stiff and artificial. Consider Tarzan swinging through vines—his trajectory is a graceful arc that feels weighty and smooth. Practicing arcs sharpens your eye for realistic flow.

8. Secondary Action

Secondary actions support the main action. A head turn feels more alive if paired with a blink or a shifting hand. They add depth, not distraction. In Coco, Miguel flicks subtle shoulder shifts and toe taps that underline his playing without pulling focus from the strum.

Secondary actions give your characters texture. They keep the audience’s eye engaged while reinforcing the main story beat.

9. Timing

Timing is the soul of animation. It’s not just how long something takes, but how that rhythm creates emotion. Fewer frames mean snappy, comedic timing; more frames create drama or gravity. In Kung Fu Panda, Po’s quick beats create comedy, while Shifu’s slower, deliberate timing conveys wisdom. Mastering timing means mastering audience emotion.

10. Exaggeration

Exaggeration amplifies emotion or motion without breaking believability. A sad character doesn’t just frown—they slump, droop, and sigh. Pixar’s Inside Out pushes Joy’s expressions further than real life, but it works because it highlights her personality. Exaggeration ensures your audience feels the moment rather than just observing it.

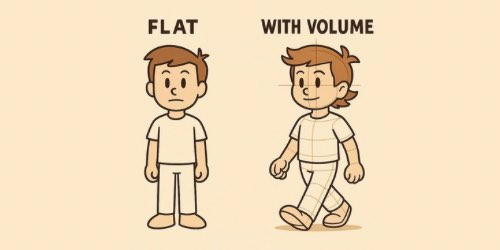

11. Solid Drawing

Even in digital animation, solid drawing matters. Characters need volume, balance, and consistent proportions. Think of it as giving them bones under the skin. Without this, characters slide off-model or look flat. In Spider-Man: Into the Spider-Verse, each character style is unique, but they’re grounded by consistent anatomy and weight.

Practicing solid drawing—even with quick sketches—gives you confidence and clarity in your animation.

12. Appeal

Appeal is the invisible charm that makes characters engaging. It’s not about cuteness; villains can have appeal, too. It’s about clarity, charisma, and design that invites the viewer in. Baymax in Big Hero 6 is simple, round, and soft—yet incredibly appealing. Clear silhouettes and readable gestures make us connect immediately.

How to Practice These as a Beginner

Start with simple exercises. Animate a bouncing ball (squash and stretch), a character waving (arcs and timing), or a walk cycle (follow-through and overlapping action). Don’t try to master all 12 at once. Focus on one or two per project. With repetition, they’ll become second nature.

Final Thoughts

The 12 Principles aren’t just theory—they’re what transform still images into living performances. Apply them step by step, and your animations will not just move, but breathe. Each principle is a stepping stone toward creating characters that audiences believe in and care about. Over time, practicing them will give your animations a life of their own.

Treat this final visual as a mini-drill: pick one principle, set a short timer, and build a tiny loop that demonstrates it; consistency will turn these ideas into instinct.